Natural gas flourishes in Pennsylvania, guaranteeing less expensive, cleaner-burning fuel, steady employment, and the likelihood of the U.S. becoming free of foreign oil. But could it be the seeming cost of all these?

The small town of Dimock, Pennsylvania, home to around 1,500 individuals, has probably the best-producing Marcellus wells in the state. It is presently popular around the world. But not for the reasons a portion of the townsfolk would like.

The name Dimock has become inseparable from flaming taps and everything that might go wrong when the gas drillers come to town. However, the battle over Dimock's water and reputation has isolated the town.

The town of Dimock, Pennsylvania, has been the center of controversy over the environmental effect of hydraulic fracturing. Residents of Dimock depend on groundwater, and in 2009, they had to acquire substitute sources due to contamination of their groundwater, which they accused of wells drilled by Cabot.

The affected residents claim that gas drilling has contaminated residential drinking water wells. Cabot had drilled and fracked 62 wells in a nine-square-mile area around Dimock. Cabot denied that their wells were liable for the contamination. Dimock featured notably in the anti-fracking "documentary" Gasland.

Residents Speak

One of Dimock's residents and a retired school teacher, Victoria Switzer, said in a 2012 post at StateImpact Pennsylvania that gas drilling poisoned her water with methane and drilling chemicals. Although, some of her neighbors have averted against her. She just wanted her well to be safe and protected.

Switzer added that Cabot Oil and Gas, which came to drill six years ago, won't assume a sense of ownership regarding water supply damage.

Since the contamination surfaced in 2009, state regulators have prohibited the company from drilling or finishing any new wells in the town. Also, Switzer concluded that some in Dimock blamed her and the ten families suing the gas company.

An encounter that is never forgotten.

Dimock's gas boom started in 2006 when landmen began knocking on doors, eager to buy the residents' mineral rights and drill for natural gas. Victoria Switzer was building her dream home.

Jim Grimsley, another Dimock resident, remembers the day, too. At that point, they thought they were getting a very decent arrangement. The person who knocks on your doors is a decent talker and sharp, so they signed.

The residents continued that the one thing everyone settled on: The landmen were not completely honest. Cabot purchased mineral rights in Dimock for $25 an acre. Afterward, similar deals in nearby towns cost $4,000 to $5,000 an acre.

That is the part where settlement on natural gas drilling and relations with Cabot appear to end.

Here's the place where the residents encounter differences from each other.

After the drilling started, Switzer says she saw changes in the quality of her well water. It became foamy and dim, with an unrecognizable smell, and orange.

At different times, it looked like Alka Seltzer. The changes travel everywhere. Switzer says private water tests have shown ethylene glycol and undeniable degrees of methane. She says she attempted to work with Cabot, but it was for nothing.

Switzer continued that they were arrogant and mean, and they said to sue them, and they'll lose. So Switzer joined the lawsuit due to what she calls a lopsided battle.

Alert the Media

Due to the residents' frustrations, they decided to call the local newspaper. They thought that of all the help they asked from the gas company, the elected officials, and the DEP, they were not heard until the media got things done.

Before long, TV cameras from as distant as Germany and Japan arrived at Dimock's doorstep. Furthermore, a few neighbors said the coverage was totally out of line. Even though Teel says she disapproved of her drinking water, Cabot was very responsive.

The residents who complained all sold their mineral rights and received royalties from gas drilling. Switzer said she was not against natural gas extraction, but the subsequent terrible water had been a huge cost.

Cabot has eight wells on one of the residents' properties. Drilling impacted the water from the start, clogging lines with sediment.

DEP To the Rescue (Or Not)

Nine months after a resident's water well exploded in January 2009, the state Department of Environmental Protection referred Cabot for flawed good construction. DEP said Cabot's work contributed to methane migration into the aquifer.

The DEP never said deep fracking contaminated the water; it just said methane escaped from certain gas wells and streamed into the spring. Several consent orders followed.

One ordered Cabot to provide residents with water. After a year, in November 2010, the state vowed to pipe in treated water from a nearby town. Authorities said they would force Cabot to compensate the state for the expenses, regardless of whether this implied suing the company.

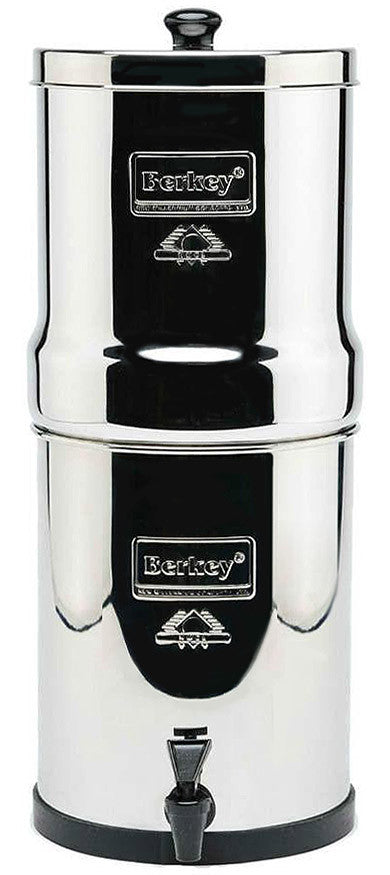

However, a month later, that plan was scrapped. Instead, the DEP arranged a financial settlement directly with Cabot, which incorporated establishing a water filtration system.

Those suing Cabot, like Switzer, dismissed the arrangement as insufficient. However, some residents accepted it, which caused another rift.

What is next for Dimock?

The residents believe that the issue is not media hype. It is what's doing right. Some said they would never trust the water from their tap again.

As far as it matters for Jim, Grimsley says he couldn't say whether some water wells are as yet polluted or not, and he couldn't say whether Cabot is mindful. However, he contends that, in any case, the damage to the local area is done.

Cabot says its drilling operation didn't pollute Dimock's aquifer. Company representative George Stark says undeniable degrees of methane have consistently existed in Dimock's water wells. Their one misstep, says Stark, is not directing pre-drill tests for methane.

Since 2009, state environmental regulators have repeatedly cited Cabot Oil and Gas for infringement in the town of Dimock. In November 2011, the DEP permitted Cabot to stop providing clean water to residents along Carter Road.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency entered the debate, consenting to provide water to three households and leading its water testing. The federal agency has gathered water samples from around 60 households.

Up until this point, it has let outcomes out of 11 households. The EPA says it has observed nothing in those tests that should keep anybody drinking the water. However, researchers consulted by the actual residents themselves dispute that conclusion.

← Older Post Newer Post →