Most of us drink tap water without thinking twice. If it comes from the faucet and looks clean, we assume it is good to go.

Of course, treated water does protect us against many harmful microbes. There's one part of the treatment process that many individuals are unfamiliar with, though. It's something that creates disinfection byproducts, or DBPs.

DBPs form when chlorine reacts with natural organic matter still present in the water. This might be tiny bits of plants, soil, or anything organic that the system did not remove completely.

When the chlorine reacts with these materials, small chemical compounds can form. They aren't added on purpose. They occur because of how the process works.

You won't see DBPs in the water, and you won't taste them either. But they're present in small quantities, and they're among the things water providers monitor.

For many people, the first time they hear about DBPs is when they read their local water report or happen upon the term on the Internet.

Then the questions begin. What are these compounds? Should I be concerned about them? Can a filter help? Must I do anything differently at home?

IN THIS ARTICLE, we will answer all of that in plain language. We will go over what DBPs are and why they show up in treated water.

We will look at the most common types you might see in reports—things like trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids. But we'll talk more about it later.

There is also a quick look at the health concerns researchers watch and the limits set by regulators. After that, you will see how specific filters can help reduce DBPs. We will wrap up with simple steps you can take to lower your exposure at home.

What Are Disinfection By-Products (DBPs)?

The term disinfection byproducts sounds quite technical. But the basic concept isn't too complicated.

DBPs are simply the small compounds that form when a disinfectant meets natural organic matter in water. This organic matter generally comes from plants, soil, leaves, and other similar natural materials that turn up in rivers and lakes.

So yes, these surface water supplies feed many public water systems. Water systems use disinfectants to kill waterborne bacteria and thereby stop diseases like typhoid fever.

Chlorine is the most common. However, other disinfectants include chloramine, chlorine dioxide, and ozone. All the above contribute to making drinking water safer.

However, these same disinfectants can form byproducts. And that's when they react with naturally occurring organic matter and even minerals like bromide or iodide.

These are the disinfection by-products that people talk about today. Or probably what you've heard of.

This reaction can occur in a treatment plant, in the distribution system, and even in storage tanks as water age increases. The longer the water sits around the system, the greater the chances these compounds will form.

You will not see them in your tap water. But they do form part of the treatment process, especially in chlorinated drinking water.

In all, researchers have identified more than 600 DBPs to date. Some estimates put it closer to seven hundred. That's a lot, right?

But only a small group is tracked in community water systems. Why so? Testing every single compound would be too expensive and too technical for most water utilities.

For this reason, the focus remains on regulated DBPs, such as total trihalomethanes and the five haloacetic acids (HAA5), including trichloroacetic acid and dichloroacetic acid.

These groups are associated with potential health risks with long-term exposure. That is why they are listed in DBP regulations under the Environmental Protection Agency. Actually, the World Health Organization also sets guidance values for public health protection.

The United States is required to have a maximum contaminant level for the primary regulated DBPs by the Environmental Protection Agency EPA. Water utilities are required to take DBP samples at sample points across the system.

They also adhere to rules like Stage 2 of the disinfection byproducts rules. These rules check the location-based running annual average to ensure each part of the system stays under the limit.

If levels rise or a system exceeds the standard, the community receives a public notice from the Department of Health or its local water provider. As you can see, the objective of ALL this monitoring is pretty straightforward.

Disinfect water to protect public health while maintaining DBP levels as low as possible. Utilities also "change" the treatment process. And, of course, they occasionally experiment with alternative disinfectants to reduce formation.

There is no single perfect approach. Each water source has different organic materials and conditions.

The key concept, however, remains the same everywhere. It's all typical, really. Kill harmful microbes, control harmful health effects, and keep drinking water supplies safe in the long term.

Common Types of Disinfection Byproducts You Should Know

• Trihalomethanes THMs or Total Trihalomethanes TTHMs

Trihalomethanes are a class of volatile organic chemicals. They are formed when chlorine "interacts" with naturally occurring organic matter.

One thing to note, though. They are particularly prevalent in water systems that rely primarily on chlorine as a disinfectant.

THMs can be formed within the treatment plant. And so, they continue their formation as water moves through the distribution system. Water age is another factor.

Older water in long pipelines or storage tanks can show higher levels because the reaction has more time to occur.

The most common THMs are chloroform, bromodichloromethane, dibromochloromethane, and bromoform. Many water utilities report these as “total trihalomethanes” (TTHMs).

TTHMs are often the most abundant DBPs by mass in treated water. Because of that, they are a big part of DBP regulations set by the Environmental Protection Agency EPA.

People often watch TTHMs because long-term exposure may increase the risk of cancer. That is why the Environmental Protection Agency.

Not just them, though, the World Health Organization also includes THMs in their public health guidelines. Most systems stay within low levels. But, to be sure, they still test because THMs form so easily when organic matter is present.

• Haloacetic Acids HAAs, particularly HAA5

The next group is haloacetic acids. These form during the same treatment process. But they behave a bit differently.

HAAs are less volatile than THMs, so they do not evaporate as easily. They stay in the water itself. Many water utilities monitor the HAA5 group.

This group includes monochloroacetic acid, dichloroacetic acid, trichloroacetic acid, monobromoacetic acid, and dibromoacetic acid.

Similar to THMs, these acids are formed when disinfectants react with natural organic matter in drinking water sources. Because they remain dissolved, they can accumulate in areas of the system with older water.

They can also appear more often when the source waters are surface waters. And most especially if they appear in greater amounts of organic material.

The Environmental Protection Agency sets a maximum contaminant level for HAA5. Water utilities test these regularly, along with TTHMs. If a system exceeds the limit, the community receives a public notice from the Department of Health.

The rules fall under the EPA’s disinfection byproducts rules. Between them, there are Stage 2 requirements for community water systems.

• Other DBPs regulated or emerging

Other disinfection byproducts also appear in drinking water. Some of these are regulated in certain places.

Examples include bromate, which may form when ozone is used as a disinfectant, and chlorite, which may form when chlorine dioxide is used in the treatment process.

Here's another thing to note. Researchers have identified many other DBPs that form in small amounts.

These include haloacetonitriles, haloketones, halonitromethanes, haloaldehydes, nitrogenous DBPs, iodinated compounds, and other dbps that appear under specific conditions.

These are all serious. Several laboratory studies have shown that some unregulated DBPs may be more toxic than common DBPs.

Because they occur only at low levels (and are more difficult to measure), most drinking water regulations are initially set for the main groups.

Health Risks Associated with DBPs

Most of the time, tap water is safe. That's true for most homes. Water is disinfected to kill bacteria and viruses.

But when disinfectants such as chlorine, chloramine, chlorine dioxide, or ozone react with natural organic matter in water, they form DBPs.

That organic matter comes from leaves, plants, and soil. And really, anything that gets into rivers or lakes. So, we can't rest assured.

Certain DBPs remain in water after treatment. Long-term exposures have been associated with increased risk of bladder or colon cancer. And that's not all, they also indicate impacts on reproductive health or development.

The evidence for these claims is minimal for now. But, should we really take the risk?

Exposure to DBPs does not occur through drinking alone. Volatile DBPs, such as chloroform, can be released into the air during showering or bathing. Some DBPs can even be absorbed through the skin.

Lab studies show that many DBPs are known to cause cell or DNA damage. That sounds scary, we know. But honestly, most public water systems keep DBP levels low.

It's why public health agencies monitor them, and utilities run regular tests on drinking water supplies—monitoring and treatment work to balance safety from microbes with reductions in DBPs.

Regulatory Standards and Monitoring

EPA sets limits for the most common DBPs. TTHMs have an MCL of 80 micrograms per liter. HAA5 has a limit of 60 micrograms per liter.

Public water systems are required to comply with Stage 1 and Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproducts Rules. Utilities test at different locations in the distribution system.

They take an average over the year and ensure their levels are below the limit. If they are above the limit, the system issues a public notification. That's how it works.

Monitoring broadly covers the major DBPs, such as TTHMs and HAA5, as well as a few inorganic by-products. Hundreds more DBPs are formed, and most are neither measured nor regulated.

Some unregulated DBPs may even be more toxic. But sadly, we don't know enough yet. Water treatment is a balancing act, after all.

If too little disinfectant is applied, people get sick from waterborne bacteria. Too little or too much organic matter in the water, and DBPs go up.

Utilities manage source water, storage tanks, and distribution systems to maintain disinfectant levels within target ranges and reduce DBP formation. Although regulations do not cover all DBPs, staying below the limits for TTHMs and HAA5 maintains exposure at reasonably low levels for most people.

Monitoring and good treatment make tap water much safer than untreated water. Knowledge of DBPs helps you decide whether additional protection (like a home filter) is proper for you.

How Water Treatment and Filtration Can Reduce DBPs

• What happens in Municipal Treatment Plants

Water utilities do a lot to keep DBPs in check before water even reaches your tap. Most DBPs form when disinfectants react with natural organic matter.

So plants try to remove that stuff first. They use coagulation and sedimentation to make particles settle out.

They filter the water and measure total organic carbon to determine how much organic material remains. The cleaner the water going into disinfection, the fewer DBPs are likely to form.

Other plants use more sophisticated techniques, including pre-ozonation followed by biological activated carbon filtration.

Membrane systems, such as nanofiltration or reverse osmosis, may also be used either before or after disinfection. These processes either remove or transform the organic material.

In turn, fewer DBPs form as water is distributed through pipes and storage tanks. We know it isn't perfect. But still, it helps balance the need to keep water free of bacteria and to minimize long-term exposure to DBPs.

• Point-of-Use (Home) Filtration

Even with good municipal treatment, many people like extra protection at home. Point-of-use filters are a simple way to reduce DBPs in tap water.

Activated carbon filters are standard. They can be either granular carbon or carbon block and remove many DBPs, including THMs and HAA5, as well as their precursors.

Their efficacy depends on the filter itself, water quality, flow, and how often you replace it.

Reverse osmosis or nanofiltration systems remove even more. They cut both regulated and some unregulated DBPs, among other contaminants.

Studies show RO can reduce DBPs by over 98 percent. Carbon filters are more variable but still useful.

RO is better for those whose water comes from a surface source or has more natural organic matter. Carbon filters work fine for everyday use.

The key is to keep filters maintained. Old or clogged filters don't remove DBPs effectively.

• Trade-offs and Things to Keep in Mind

Disinfection is indeed essential. If not, your water could be carrying waterborne bacteria. Or who knows? Create outbreaks of diseases such as typhoid fever.

The benefits of chlorination or other disinfectants usually outweigh the DBP risks if water is treated and monitored correctly.

No one method removes all DBPs, much less all contaminants. Home filtration helps reduce exposure, but it is not a guarantee of “pure water.”

Some of the emerging or unregulated DBPs may still be present. Reductions in THMs and HAA5 are not eliminating all the harmful compounds.

Even so, combining safe municipal treatment with a good home filter is one of the easiest ways to drink tap water that is safer and cleaner.

Practical Steps for Consumers

Worried about DBPs in your tap water? There are a few simple things you can do to reduce exposure. Don't panic just yet. Here are a few habits that can help make your water cleaner.

1. Check your local water report.

Most public water systems release an annual water quality report. It shows DBP levels, disinfectant types, and other contaminants. It’s a good way to know what’s in your drinking water supplies.

2. Use point-of-use filtration.

A carbon filter or reverse osmosis system can remove many common DBPs, including THMs and HAA5. Carbon filters are easy to install and maintain, and work well for everyday use.

RO systems remove even more but cost more and need more maintenance. Either way, filtration lowers your exposure and gives you peace of mind.

3. Let tap water sit before drinking.

Some DBPs are volatile and can evaporate. Filling a pitcher and letting it sit for a few hours can help reduce compounds like chloroform.

4. Avoid very hot showers in poorly ventilated bathrooms.

Consider this tip to reduce inhalation exposure. THMs can evaporate in the steam. Good ventilation helps a lot more than you think.

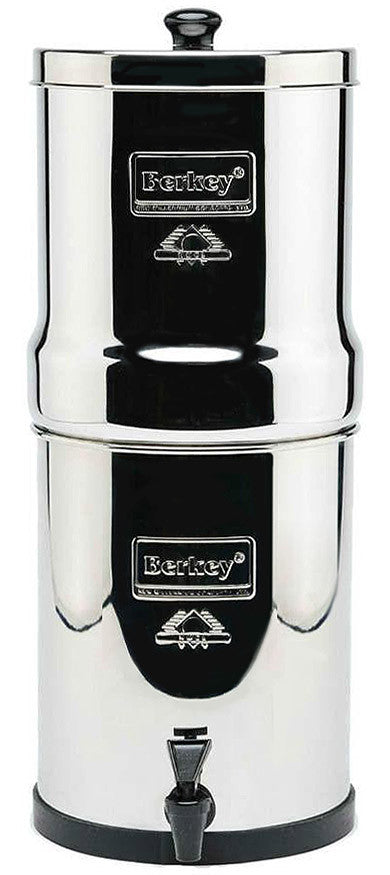

5. Consider systems like Berkey if you want extra protection.

Berkey filters use activated carbon and other filtration methods to reduce DBPs, heavy metals, and other contaminants. They’re portable, don’t need plumbing, and are popular for home use.

Again, we know they aren’t perfect. But honestly, they provide an added layer of safety for your family.

6. Stay informed.

DBPs are just one part of water quality. Knowing about your source water, how it’s treated, and what filters can do helps you make better choices.

And remember, treated tap water is still much safer than untreated water. Filtration is just a smart extra step.

Final Thoughts

Water disinfection is a necessary process. That's a significant thing to note (or acknowledge).

Otherwise, our taps would be carriers of bacteria and viruses that make people sick. For this reason, chlorination and other treatments have been implemented in public water systems.

The side effect is the formation of DBPs. Or, as discussed above, chemical by-products form during reactions. Specifically, when disinfectants and natural organic matter "meet" in the water.

Most of these compounds remain in the water and, over time, may have potential health effects. And we need to take caution. Yes, even when you don't really see them.

Most people assume tap water is automatically safe. And in most cases, it is. But again, DBPs are a hidden part of the picture, especially if you drink tap water every day for years.

Even if levels are low, long-term exposure is something you should be aware of. Understanding what DBPs are, how they are formed, and which ones are monitored can help you make smarter choices about your water.

Fortunately, practical means to reduce exposure exist. Employing activated carbon filters, reverse osmosis systems, or Berkey-style filters can eliminate many DBPs.

Simple habits will also help. You know, like allowing water to sit before drinking, ventilating bathrooms during hot showers, and keeping your filters clean and replaced on schedule. They ALL matter.

Water safety doesn't begin and end with the treatment plant. What happens after the water leaves the system is equally important.

You can drink cleaner, safer water every day by staying informed, choosing the right filtration system, and following good water habits. It's not complicated. But trust us, it'll make a difference for long-term health. For you and your family.

← Older Post Newer Post →