The water you drink every day may seem simple. But where it actually comes from makes a pretty big difference. Some people draw water from the city. Others get it from a private well in their yard. Both can be safe, but they're handled differently.

City water flows from a treatment plant before it reaches your tap. A whole team checks, cleans, and ensures it meets specific standards.

Well water does not go through any of that. It comes straight from the ground. So really, it's up to the homeowner to make sure it stays clean.

That's why it helps to know which type you have. Each one has its own set of possible problems. City water may contain chemicals left over from the cleaning process.

Well water may contain bacteria or minerals that can affect the taste. Because the problems are different, the filters you need are different as well.

IN THIS ARTICLE, we'll cover the differences between the two, what to look out for with each, how often to test your water, and what types of filters work best in each application. We will also touch on some options that address many day-to-day drinking-water needs.

What Are City Water and Well Water?

When people refer to well water versus city water, they are talking about two very different water sources. Both can provide you with safe drinking water, but the way they are handled, treated, and tested differs.

City water, otherwise known as municipal water, typically comes from major rivers, great reservoirs, lakes, or sometimes shared groundwater. These all tend to collect water from wide areas.

And yes, that includes wetlands and land where plants, animals, and even dust, sand, clay, and small grains can mix.

This is then piped into the city, where it undergoes treatment. To be more precise, this water is filtered to remove sediment, dirt, and other suspended solids. After that, chlorine or chloramine is added to the system to kill bacteria and viruses.

City water is also checked under strict rules. EPA sets standards for harmful contaminants, chemicals, and levels that public systems must meet.

Utilities publish data, test results, and state updates each year. It's really so that communities know the quality of the water being delivered through the pipes.

Well water works more directly. It originates in an aquifer, which is, for the most part, water stored underground between layers of rock, gravel, and sand.

A private well draws this up and pipes it directly into your house. There's no huge facility, no city crew, and no regular government testing.

The CDC notes that private wells aren't covered under the Safe Drinking Water Act. In other words, the homeowner must maintain the system, test it, and choose appropriate filtration methods to stay safe.

Because well water touches so much land and environment, it can pick up iron, salt, sediment, and even bacteria. Sometimes the risk is small. Sometimes it’s dangerous.

That all depends on where you live, your soil, and what’s around your property. This is why many owners add a filter or treatment system to protect their health and remove contaminants.

Contamination Risks: City Water vs Well Water

|

Aspect |

City Water (Municipal) |

Well Water (Private) |

|

Source |

Surface water/reservoir, treated |

Groundwater/aquifer, untreated/raw |

|

Regulation & Testing |

Utility-regulated, regular testing (EPA) |

Owner responsibility; no federal mandate |

|

Common Contaminants |

Chlorine, lead, disinfection byproducts, PFAS |

Bacteria, nitrates, iron, arsenic, sulfur |

|

Testing Frequency |

Utility tests, consumer reads report |

Annual + event-based testing |

|

Typical Treatment |

Carbon filters, RO, whole-house filters |

Multi-stage (sediment, UV, media, RO) |

Comparing well water vs city water is pretty straightforward. The most significant differences generally emerge in the kinds of contaminants each is capable of carrying. Either source may be safe. But of course, each has its own set of problems to watch out for.

Some come from the environment, some from old pipes, and some from the surrounding land use. Knowing the risks will help you choose the right filter or treatment system for your house.

Common Contaminants in City Water

City water goes through treatment, but it doesn't come out perfect. It still picks up several things along the way.

1. Disinfectants and residuals

Utilities add chlorine or chloramine to kill the bacteria and viruses in the water.

The downfall is the leftover smell and taste. Some individuals are sensitive to these chemicals, especially when drinking water daily.

2. Disinfection byproducts

When chlorine reacts with naturally occurring materials, such as leaves, dirt, or plant particles, disinfection byproducts such as THMs may form.

The levels are generally within safe limits, but many households would nonetheless like to reduce them through filtration.

3. Heavy metals from pipes

The city might be treating the water well, but it has to travel miles through aging pipes. Old plumbing releases lead and copper, especially in older neighborhoods.

Those homes built decades ago run an increased risk. This is one of the significant factors that makes people look into home filters rather than just relying on the public system.

4. Emerging contaminants

Other newer concerns include PFAS, industrial chemicals, and traces of pharmaceuticals.

They don't always have a taste or smell, so testing and routine filtration are becoming more common.

Common Contaminants in Well Water

Well water offers a more “natural” source, but that doesn’t mean it’s clean. Since it comes from an underground aquifer, it comes into contact with soil, clay, rock, and everything in the surrounding land.

The EPA lists the most common problems homeowners should watch for.

1. Microbial pathogens

E. coli, coliform bacteria, viruses, and protozoa can be carried by wells. These microorganisms may enter the well through surface runoff, floods, or cracks. They most often originate from nearby animals, septic systems, or heavy rain.

2. Nitrogen compounds

Nitrates and nitrites come from fertilizer, agriculture, and leaking septic tanks. The EPA warns that these can be dangerous for infants, causing a condition called "blue baby syndrome."

These compounds have no taste or smell, so you can't detect them without testing.

3. Naturally occurring minerals

Many wells pull water through layers of iron, manganese, arsenic, and sulfur. Iron can leave orange stains. Manganese can turn water black.

Sulfur leaves a smell like rotten eggs. Arsenic poses an exceptionally high risk. Why? It's because it is impossible to see or taste it.

4. Changes that are seasonal or based on the weather

Well conditions can change throughout the year, according to Clear Water Filtration. Heavy rainfall, drought, and flooding can alter contaminant levels.

This would mean that the water could test clean one month and then suddenly show problems the next.

Extra Note: So, why do the risk profiles differ?

City and well systems have different problems because they are built differently.

City water is treated and monitored. However, the delivery path it takes through old pipes and tanks in a widespread system adds its own set of risks.

According to some studies, corrosion, leaks, and construction work can all affect water quality.

Well water is the opposite, though. It's unregulated and fully dependent on good well construction, good maintenance, and routine testing.

The University of Georgia's AESL program notes that two homes just a few meters apart can have completely different water results. And that's simply because wells pull from other parts of the ground.

Testing Frequency and Responsibility

• Who’s Really Responsible

With city water, the job largely falls to the local utility. They operate, maintain, and test the system on a regular schedule. Most communities publish the data online.

In a way, customers can check the state of their drinking water without doing their own testing.

With well water, the homeowner bears the cost. There's no central authority checking whether your well is safe. Nobody comes to test it on your behalf.

Honestly, it's up to you to take the steps so you know what's going into your mouth. If you want safe drinking water from a private well, regular testing is part of the deal.

• How Often You Should Test

For private wells, the standard recommendation is to test at least once per year. That typical annual check often includes testing for bacteria, nitrates, total dissolved solids, and pH. It’s a simple way to catch the most common problems.

Some wells need more frequent testing, especially if anything changes around your home. If the water suddenly tastes funny, smells like rotten eggs, or looks cloudy, that's a hint. So, please don't ignore it.

Flooding, heavy rain, or land changes can also increase the risk of contaminants entering. Even shifts in local geology can play a role, depending on where you live.

City water customers don't need to follow the same testing schedule, as the city handles that. You can stay informed by reading the annual water quality report. Utilities often put it on their website.

• What To Look For When Testing

Well water testing generally looks at bacteria, nitrates and nitrites, metals such as arsenic, and anything else linked to the local environment. Some wells naturally bring in iron or manganese.

Others have higher sediment or dust levels, depending on the land's composition and the nature of the underlying rocks.

City water is usually tested for heavy metals, chlorine byproducts, and small amounts of chemicals or trace contaminants. If your community has discussed issues with PFAS or pipe corrosion, you can request additional tests or home test kits.

Treatment Needs and Filtration Options

Filtering City Water

City water undergoes a complete treatment process before it reaches your tap; however, many people wish to clean it at home further. The goal is generally basic. It's the removal of chlorine or chloramine, correction of taste, and reduction of the chemicals you don't want to drink.

Some households desire additional protection from lead or PFAS if their communities have had issues with pipe corrosion or other older infrastructure.

One of the most common tools is an activated carbon filter. These come in pitchers, under-sink systems, or faucet attachments. Carbon can bind to chemicals, helping reduce the "pool water" smell and taste.

For most city homes, this is enough to make the water feel smoother and more pleasant. RO forces water through a tight membrane that removes smaller contaminants. We have PFAS, heavy metals, and VOCs here.

It's stronger, yes. But also, it uses more water and takes up more space under the sink. Because it makes such spotless water, some people use RO only for drinking and cooking.

If you want your entire home covered, there are whole-house filters. These sit at the point where the water enters the house. They remove chlorine, sediment, and other chemicals before the water comes into contact with any faucet, showerhead, or appliance.

It is convenient for people who want better taste throughout and not just at the kitchen sink.

Treating Well Water

Well water's a different story altogether. City water arrives treated, whereas well water arrives as nature delivers it. And nature can mix into that all kinds of things.

Quite literally. We have sediment, bacteria, minerals, and random contaminants depending on the land around your property. Because of that, well owners usually need a multi-stage system rather than just one filter.

A typical configuration would start with sediment or a pre-filter. This is the one that catches sand, dirt, clay, and other grains picked up underground. If this step is not done, the finer filters downstream clog up too quickly.

Some wells also use a media filter, such as sand or anthracite. These systems trap more particulates and help clean the water before it moves to the rest of the treatment line.

Another important layer is disinfection. Many homes choose UV light because it kills bacteria and viruses without using chemicals. Others use chlorination systems if their water has recurring microbial problems.

Iron and manganese can be present in many wells. Ion exchange systems or special filters can handle these minerals, so the water doesn’t smell metallic or stain sinks and clothes.

Some people also add carbon or even reverse osmosis for specific chemical reductions or taste improvements. Hardness is also typical in private wells.

A softener reduces scale, which minimizes the buildup of white deposits in pipes, appliances, and shower fixtures over time.

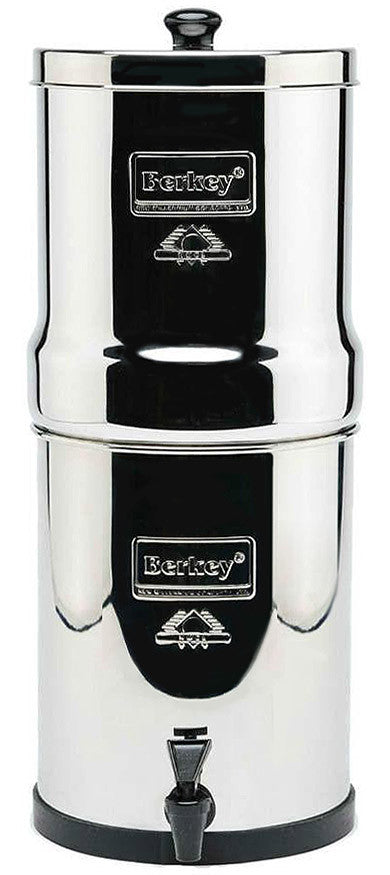

Using Gravity Filters — Berkey

Many households like having a gravity-fed filter on the counter, and one of the most well-known options is the Berkey. It doesn't need electricity or plumbing, so it's easy to use anywhere. You pour water in, gravity pulls it down, and the filter elements do the work.

The Black Berkey elements can remove a wide range of contaminants, including heavy metals, VOCs, pesticides, and some microbial contaminants. There are also optional fluoride and arsenic filters that attach to the bottom for more coverage.

For city water, Berkey works as a taste upgrade. It helps reduce chlorine, odor, and some of the chemicals that slip through the municipal process.

Many people use it as their primary drinking water filter because it's simple and sits right on the counter. Berkey works best for well water when it's the final "polish."

Safety Considerations and Best Practices

Before buying any filter, test your water first. It's hard to fix a problem you haven't actually identified, and guessing usually leads to the wrong setup.

A certified lab or a reliable home kit can show you what you're dealing with-bacteria, chlorine, minerals, metals, or whatever is slipping into your system.

Once you know what's in your water, match the treatment to the issue. Some people install a huge system they don't even need.

Others underfilter and end up with problems later. A good setup is the one that fits your actual water quality, not the one that looks the most advanced.

Maintenance is crucial, too. Filters don't last forever. Cartridges clog, media gets dirty, and systems slow down if you ignore them.

Replacing parts on schedule keeps everything working and protects your health. A clean filter is always better than a "still working, but kind of overdue" filter.

• For Well Water Owners

Wells require much more manual maintenance. It is a good idea to disinfect the well from time to time, particularly after storms or flooding. Floodwater can bring in sediment, bacteria, or dirt that wasn't previously there.

The well area should remain clean. Do not store chemicals near the well, and monitor septic systems. A small leak can become a significant contamination problem far quicker than you might imagine.

Most well owners benefit from a multi-barrier setup. We have a pre-filter, disinfection, media layering if necessary, and a point-of-use filter for drinking. Each stage removes a different type of contaminant, keeping the water safe throughout the process.

Keep records of your test results, too. You'll see patterns across the months or seasons that help you catch changes early.

• For City Water Users

If you're on municipal water, check the Consumer Confidence Report once a year. Utilities post it online, and that gives a good snapshot of what's coming through the pipes.

A point-of-use filter is handy if you don't like the taste, want to reduce lead, or live in an area affected by PFAS or other emerging contaminants.

If you're on RO, don't forget to swap the membrane and flush the system to keep it efficient.

Power outages affect wells and city water systems alike. A gravity-fed filter, such as a Berkey, can keep you covered since it requires no electricity.

← Older Post Newer Post →